http://www.oldworldwandering.com/on-the-travelogue/

As usual, if printing, I suggest you cut out the pics and maybe use 11-point font to save paper!

On Travelogues

It seems as inevitable that voyaging should make men free in their minds as that settlement within a narrow horizon should make men timid and servile.

HG Wells, 1922

Agriculture brought settlement, cities and, six or seven thousand years ago, writing. Although man first wrote to keep account books, by 2600 BCE he was starting to inscribe his people’s tales in clay and stone, giving a stable, solid structure to narratives told loosely by earlier men. Writing made final what had been fluid before, which suited man’s new stability and the growing scale of his society, and like everybody who has sought a place in the world since, the first writers were primarily concerned with explaining their origins.

The oldest story long enough to enter literature’s canon is The Epic of Gilgamesh, a legend written in cuneiform that was lost until 1853, when it was found amongst the ruins of Nineveh, in what is now Iraq. The epic has a cast of hideous, spiteful monsters, petty gods, whimpering mortals and, in its protagonist, a tyrant – Gilgamesh, the King of Uruk, who is only two-thirds divine and as a result must die. The tale legitimises the rule of a heroic, godly despot over sedentary men, but the wanderer is not far gone, and the world’s first work of literature is mostly a travelogue, describing a journey to the known world’s end in search of eternal life.

Uruk’s citizens are treated badly by Gilgamesh at the start of the epic. He takes newlywed women to his bed by sovereign right and works the city’s men to the bone. Fed up, the people pray to the Mesopotamian gods and are heard: the gods distract the king by creating a companion for him – Enkidu, a primitive man covered in hair who “lives in the wild with the animals”. A man who is, in short, a wanderer. Enkidu is soon seduced by civilisation, quite literally: an accomplished temple prostitute is sent to him and after seven days of love making the two return to Uruk, where Enkidu becomes a shepherd. At his shepherds camp, Enkidu learns that Gilgamesh takes brides to his bed and, because he is still a man of pure, unfettered freedom – a symbol, in many ways, of the unbound people before civilisation – the practice enrages him. He goes to confront Gilgamesh and the two come to blows at the entrance to a wedding chamber. It is a fierce, close fought contest, but Enkidu is eventually bettered by the demigod. The tussle establishes mutual respect and the men become friends; later, after Gilgamesh’s mother adopts Enkidu, they become brothers. Together they travel to the Cedar Forest to kill its guardian, a hideous ogre who wears seven suits of armour, and together, by giving each other courage at critical moments, they succeed. As he lies dying, the ogre curses Enkidu. “Of you two,” he says, “may Enkidu not live the longer. May Enkidu not find any peace in this world!”

Enkidu is a creature of the gods, and for his temerity the gods take his life. He falls ill. Days later, he dies. Gilgamesh is left broken hearted and alone, but his short relationship with the wanderer has both ennobled the king and instilled in him an obsessive fear of death, and the rest of the epic is a description of Gilgamesh travelling, at first aimlessly through the wild clad in animal skins, while he mourns Enkidu, and later in search of Utnapishtim, the Mesopotamian equivalent of Noah, who was granted immortality for ensuring that life on land survived the deluge that is perhaps mankind’s most entrenched myth. Although Gilgamesh eventually finds Utnapishtim, he learns that his immortality was a once-off. Gilgamesh will die – but in the subtitle of the epic that is his story, He Who Saw the Deep, he lives on, and the Sumerians credited Gilgamesh with bringing back from his journey knowledge of how to worship the gods and how to be a just king, as well as an explanation for the mortality of men and the essence of living a good life.

John William Waterhouse's 1891 depiction of Odysseus and the sirens

Early travelogues are mixed up with religion, and Odysseus’ story is no different. He is repeatedly obstructed by the sea god Poseidon and the last of his men perish after slaughtering the cattle of Hyperion, the sun god. Not all the gods persecute Odysseus: he is assisted by Athena, the daughter of Zeus, who appears at intervals throughout the narrative, but ultimately The Odyssey is not a religious story. Odysseus is considered the “peer of Zeus in counsel” and his cunning is unrivalled. Homer repeatedly invokes the epithets “resourceful” and “wise” to describe him and, in the end, Odysseus survives in spite of the gods, among foreign people in hostile lands, because of his individual gifts.

Writing about later travelogues, Paul Theroux hones in on individuality, and in it he identifies much of what makes the travel narrative valuable. “The writers of this time,” he says, referring to the supposed high water mark of travel writing in the 1930s, “sought to prove their own singularity by placing themselves in stark relief against a landscape that was primitive, or dangerous, or laughable, but in any case emphatically foreign.” Theroux might have cast his gaze back much further, because the rootless wanderer has always been a singular creature. It is not only that he is an outsider, a person with alien habits wearing alien clothes; what is more important – and more interesting – is that without the comfort of a neatly defined social role, or the safety of a civilisational context into which he can slot, the wanderer must define himself without comparisons to other people, except to say that they are tied to this place and I am not.

The travel writer emerges from this analysis a paradox, torn between his journey and his role as a journalist. He is both a wanderer, unbound, and a man with an audience, borrowing from the literary traditions of his culture. It is a divide he must straddle alone, and the travelogue is, in this sense, a link between settlement, with its child, writing, and the earlier world of nomadism.

Both The Epic of Gilgamesh and Homer’s Odyssey are myths, written generations after the protagonists died – if Gilgamesh and Odysseus ever lived. Greek and Roman travellers surveyed the known world, but stayed within cultural boundaries, like the geographer Pausanias, or only moved past it as part of an army, like Xenophon and Julius Caesar. Pilgrimage motivated people to travel alone to faraway places – spirituality is, after all, an individual pursuit – but for the fervent pilgrim, moving among his religious brothers, the destination is never an entirely foreign place. The Chinese Buddhists Faxian and Xuanzang travelled to India in the fifth and seventh centuries; neither wrote a description of his journey, but by relay, through other monks, a record of their experiences was preserved. Xuanzang spent five years at Nalanda, in modern Bihar. He was enraptured by the monastic city and its university, which contained a vast library – so vast that when it was razed by an Afghan army, centuries later, “smoke from the burning manuscripts hung for days like a dark pall over the low hills.” Xuanzang mastered Sanskrit at Nalanda; he bettered five hundred Brahmins, Jains, and heterodox Buddhists in debate and was offered a senior position on the university’s staff. Instead of accepting the offer, Xuanzang chose to return to China with a horde of sacred texts and relics. He translated the former, leaving behind the only copies to survive the destruction of Nalanda, and in time Xuanzang’s translations became the foundation of an idea that would itself travel: Zen Buddhism.

The two greatest

travelogues of the Middle Ages were at first either dismissed as fiction

or ignored. The story Marco Polo told Rustichello of Pisa in 1298, when

the men shared a prison cell, was derided as the blather of a

self-aggrandising con-artist because of both the outrageous success of

Polo’s journey and the poverty of Western curiosity when it appeared.

Polo travelled overland from the Mediterranean’s eastern shore to

Khanbaliq, the Great Khan’s capital then and, by a different name, the

capital of modern China today. He spent almost twenty years in the

service of Kublai Khan, travelling across his empire as an emissary, and

only returned to Venice when the Khan was old and near death, because

he feared reprisal in the political turmoil that was sure to follow.

Polo journeyed wider and deeper than modern men – with all the

advantages of convenience and predictability – almost ever dare, and if

Kublai Kahn had been a younger man, Polo might never have returned, and

might never have told his story. True wanderers rarely do.

Although

he travelled further than Marco Polo, covering a distance that nobody

would surpass until the invention of the steamship, Ibn Batutta’s

travelogue was largely ignored until the nineteenth century, when it was

translated by European Orientalists. Batutta set out from Morocco on

the hajj in 1325. He arrived at Mecca a year and a half later and, with his religious duty done, decided to join a caravan of hajjis

returning to Iraq. Travel would become the whole purpose of Batutta’s

life. He branched off from the caravan to Persia, followed trade winds

to the coast of East Africa, joined the nomadic court of the Golden

Horde, met the Byzantine emperor at Constantinople, benefited from the

patronage of Delhi’s fickle sultan, reached China, where he travelled up

the Grand Canal, and eventually returned to Morocco in 1349, 24 years

later. Even then, Batutta continued moving, reaching Granada in 1351 and

Timbuktu in 1353. He was more like a modern tourist than Polo, who was

from a family of merchants and was, at least in part, a fortune seeker.

Batutta carried his conservatism with him, castigating Turkish women for

speaking plainly to men and the women of the Maldives for their

revealing dress. He was employed for short periods, as a judge and an

advisor on Sharia Law, but normally chose his destinations on a whim. If

he could join a caravan or heard tales of wealth and wonder, Batutta

packed and went, travelling for travel’s sake. He spent a single night

in places it took him weeks to reach, and in the full title of the book

he was instructed to dictate to a scribe by the Sultan of Tangiers,

Batutta gave a hint of his nomadic soul: A Gift to Those Who Contemplate the Wonders of Cities and the Marvels of Travelling.

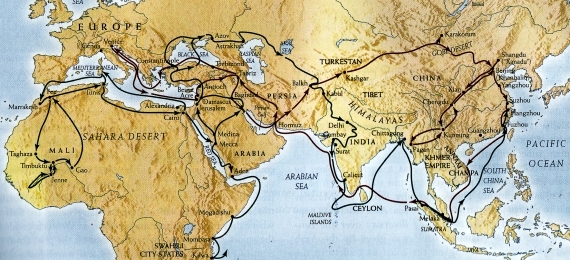

A map of Marco Polo and Ibn Batutta's routes through the Old World. Click on the image for a larger version.

Arrival, for Columbus, was empty of its normal joys. Like the other explorers of his age, he was completely filled by the idea of his own civilisation; there was no space left for the habits and beliefs of others. The travelogue is not normally a tale of conquest, and with a single exception – Fernão Mendes Pinto’s simply told Peregrinations – the Age of Exploration (and Expropriation) produced little travel writing of lasting value. But the world had started to shrink, and in some of the places that explorers had planted their flags, it was easier for writers to wander.

Only, the writer did not really exist yet. Men wrote and books were transcribed – normally at exorbitant cost, on the pelts of hundreds and sometimes thousands of calves – but the market for words was small. It depended on the same institutions that had stunted Columbus’ curiosity, the church and the king, with their loyal scribes – institutions rooted in the sedentary world. Gutenberg’s printing press, invented 37 years before Columbus arrived in the Bahamas, ate away at the institutional monopoly on words, but a class of men called writers did not properly emerge until the first copyright laws were passed in the eighteenth century, by governments scrambling to control the explosion of opinion and dissent that printing had enabled.

The professional writer was and still is a person with a single bond: his readers. If readers were interested in descriptions of a place, the writer could give in to his nomadism and go, and travelogues were among the first bestsellers. In 1727, Daniel Defoe, whose Robinson Crusoe is considered the first novel written in English, completed the third volume of his travelogue A tour thro’ the whole island of Great Britain. Samuel Johnson’s A Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland was published in 1775, twenty years after his definitive English dictionary. Goethe’s description of his Italian Journey, published in 1817, includes his still quoted awe at Michelangelo’s frescoes in the Sistine Chapel. “Without having seen the Sistine Chapel,” he wrote, “one can form no appreciable idea of what one man is capable of achieving”. Dickens also wrote about Italy, putting together a series of picturesque essays that were first published in 1846. Mark Twain paid a debt of $100,000 by embarking on a lecture tour across the British Empire in 1895, which he described in Following the Equator, and in 1899, Rudyard Kipling griped about everywhere that wasn’t India in From Sea to Sea. Lord Byron, Gustave Flaubert, Robert Louis Stevenson, Henry James, Herman Melville: all wrote travelogues as well as the defining fiction and poetry of the nineteenth century, and all were a part of the new class of professionals called writers.

A journey fits neatly into the format of a book: it has the prologue of departure and the epilogue of return, as well as the new beginnings of the next chapter and another place. Printing transformed books. It made them cheaper, putting descriptions of a wider world in the hands of middle-class Europeans, along with heretical beliefs and revolutionary ideas. It killed Latin, but made it possible to print the dictionaries that formalised other, modern languages. It created the novel, replacing the inane heroism of romantic literature with slowly unfolding inner worlds, inhabited by people who were realistically sketched. It changed travelogues too. Like novels, they turned inward and made less space for the fantastic. In 1486, Bernhard von Breydenbach could claim to have spotted a unicorn in the hills outside Jerusalem and expect to be believed, but by 1879, when Robert Louis Stevenson’s Travels with Donkey in the Cévennes was first published, unfamiliar landscapes and people were most interesting because of the effect they had on individual emotions. “For my part,” wrote Stevens, “I travel not to go anywhere, but to go. I travel for travel’s sake. The great affair is to move; to feel the needs and hitches of our life more nearly; to come down off this feather-bed of civilisation, and find the globe granite underfoot and strewn with cutting flints.”

People no longer wrote ‘Here be dragons’

on maps, and travellers could no longer return claiming to have found

them. Confined to what was real, or at least realistic, travel writers

started to produce useful history. When I compiled Tales of Old Singapore,

I sifted through thousands of sources. I looked at old postcards,

government notices, newspaper reports and the ledgers that tallied

Singapore’s trade, but the most compelling descriptions, the

descriptions that breathed life into a vanished world, were almost

always written by people passing through. Singapore might have been an

exception – it was, in the words of Charles Hendley, “a clearing house

for travellers” – but if the past is in fact a foreign country, it makes

sense that travel writers, translating their experiences for a

readership at home, would make the best guides.

Travelogues were not just written by explorers and travelling authors anymore. Anybody with the means to take a long holiday could record the experience and hope, not too optimistically, that it would be published. The number and variety of travelogues that describe Singapore after 1869, when the Suez Canal opened, is a large part of what makes these outsiders’ perspectives useful to historians, but in Charles Hendley’s use of the term clearing house, and in the countless descriptions of the Raffles and Europa hotels, where everybody stayed if they could afford to, there is a hint of the monotonous industrialisation of travel that plagues wanderers today.

Another of the nineteenth century’s new technologies transformed both how we travel and the travelogue: photography. The first photograph was taken in 1826. By 1849, men were lugging camera equipment out of Europe, to document the world’s most beguiling sights. Maxime Du Camp was among them. He travelled through Syria, Palestine, Egypt and Nubia with Flaubert, taking photographs as a substitute for sketches. “I had realised on my previous travels,” he said, “that I wasted much valuable time trying to draw buildings and scenery I did not care to forget…I felt I needed an instrument of precision to record my impressions.” The first cameras were unwieldy, hugely impractical contraptions, and wandering with them was initially impossible. “Learning photography is an easy matter,” said Du Camp. “Transporting the equipment by mule, camel or human porters is a serious problem.” In India, Samuel Bourne, another of travel photography’s pioneers, employed as many as fifty porters to carry his bulky camera along with the chemicals and plates he needed to operate it.

The cart Roger Fenton used to carry photographic equipment during the Crimean War

Wandering does not fit neatly into a frame. It is neither entirely external, like a photograph, nor completely ephemeral. In his journey, the wanderer possesses a strand that connects yesterday with today and one place with another, but photography captures without context. It is a momentary medium that can only represent fragments of any dimension, including time. Samuel Bourne recognised at least one of these limitations in the Himalaya, while on an expedition to photograph the source of the Ganges. “With scenery like this,” he wrote, “it is very difficult to deal with the camera: it is altogether too gigantic and stupendous to be brought within the limits imposed on photography.” Bourne also recognised how photography could train and improve the eye. “It teaches the mind to see the beauty and power of such scenes as these,” he wrote. “For my own part, I may say that before I commenced photography I did not see half the beauties in nature that I do now, and the glory and power of a precious landscape has often passed before me and left but a feeble impression on my untutored mind; but it will never be so again.”

The act of framing and exposing a photograph can, as Bourne put it, “teach the mind to see beauty,” but it more often teaches the mind to see other photographs. A photographer must break the world into fragments and moments that fit within a frame. He must think of light and movement mechanically, in terms of aperture widths and shutter speeds. If he does this often – and to be good he must – photography will completely reshape the way he processes the visual world. For pioneers like Bourne, who sometimes needed hours to complete a single exposure, this was less of a problem than it is today, when photographs are instantaneous and close to free. Bourne had porters and pack animals, but in most other ways, his method of travelling and his eye were not substantially different to an artist’s. Today, photography is more like a visual monomania, and it afflicts travellers far more than it does other groups. You see its symptoms in tourists taking a photograph of nearby people without making eye contact or saying hello, because they see what is picturesque before they see what is human. You see it in people who drown out the chirping of birds in the morning with the whir of closing shutters and, in severe cases, you see it in tourists forcing an entire journey through the viewfinder of their camcorders, replacing an experience with a manufactured memory.

A photograph of Cairo's skyline from Maxime Du Camp's 'Egypte, Nubie, Palestine, Syrie'

This prejudice is, in the majority of cases, completely justified. Too many travel blogs are facile when they are not fatuous. Blogs that function like letters to friends and family should, perhaps, be excused – even if some of the most readable travelogues of the past two centuries started life as a series of letters – but there are now well over a thousand travel blogs that actively seek an audience, and most of them are depressingly poor. They describe interactions with the travel industry instead of the larger world and are, as a result, like reading badly edited, first person Lonely Planet guides. They are self-reductive, confining their narratives to keywords popular on Google, like solo, solo female, family travel, eco-travel and round the world, which is aptly abbreviated to RTW, because most of these whistle stop gallivants are themselves extremely abbreviated. They are light on history, politics and context in general, but heavy on technically proficient but clichéd photography and vacuous best-of lists. The worst are self-congratulatory and patronising, written with enough gall to inform readers that they too can travel, usually along the same dismal beaten track as the blogger. Most of all – and most of the time – travel blogs are badly written. To capture an audience that browses instead of reading, blog posts must be short, easy to consume and frequent. As a result, there are both good and bad writers with insipid and tedious travel blogs.

There are notable exceptions – like Gary Hause, who is walking around the world, and Becky Sampson, who is riding a horse across Eurasia – but even they are distinguished less by the quality of their prose than by their ambitious journeys. There are also travel bloggers who stand out because they possess acute local knowledge, like Evan Villarrubia and Andy Keller, Mandarin speakers who spent a year cycling across China, and a handful of travel bloggers who work hard to balance writing well with chasing sponsorship and traffic, like Barbara Weibel and Theodora Sutcliffe.

It is unfair to hold individual bloggers entirely responsible for the degeneration of the travelogue. The travel industry, which likes reductive writing and best-of lists, started dictating the content of magazines and the travel pages of newspapers long before blogs existed. It is easily absorbing this new, less centralised medium now. Journeys might have fitted neatly into the format of a book, but do not fit nearly as well into the hyperlinked, asynchronous structure of the internet. The result is writing that is as fragmented as photographs, without links and transitions between countries and cultures. “Travel,” wrote Paul Theroux, “is transition,” and without it little of the wanderer or what made the travelogue literary remains.

The Odyssey is still widely read, almost 3,000 years after it was first composed, and Marco Polo is perhaps the most famous man of not just his generation, but an entire era. Brave journeys and great travel stories live on, perhaps forever, but the average blog post is written for the readers it might find on Facebook, Twitter and StumbleUpon today. To be enduring, a travelogue needs context; it needs to speak to what has come before, but most of all it needs to add to our understanding of a place and its people today. Too many travel bloggers think that they are achieving the latter by putting a hackneyed description in front of a new set of eyeballs, but the historians of the future, surveying travel blogs as they exist now, are unlikely to find much they can use.

The first men were wanderers and, because it is now possible to work remotely, in contact with people everywhere, it is easier than ever for man to wander again. The new nomads do not resemble Enkidu, who “lived in the wild with the animals.” They are too plugged in and too shaped by the settled world, but it would be nice if they, like him, were occasionally outraged and unfettered enough to fight tyrants. George Orwell and Ernest Hemingway did, with words as well as guns, and both wrote travelogues that will endure. It would be nice, too, if they made more of the connection between the journey and the journal. A blog is, after all, just a journal, and where and how you travel are just as important as what you write.

No comments:

Post a Comment